My last post,

Structural Unemployment: The Economists Just Don't Get It, generated some interesting comments. Here's an especially good one that was posted by an irate economist over at Mark Thoma's blog:

This is the second link I've seen to Mr. Ford's views on labor and technology. It needs to stop. Yes, we need to consider the interaction between the two. We do not, however, need the help of someone whose thinking is as sloppy and self-congratulatory as Ford's. Lots of work has been done on technology's influence on labor markets. Work that uses real data. Ford is essentially making the same "technology kills jobs" argument that has been around for centuries. His argument boils down to "this time it's different" and "people (economists) who don't see things exactly as I do feel threatened by my powerful view and are to be ignored."

There is a whiff of Glenn Beck in Ford's dismissal of other views.

Now, I think that saying "it needs to stop" and then comparing me to Glen Beck is a little over the top. It seems a bit unlikely that my little blog represents an existential threat to the field of economics.

The other points, however, deserve an answer: First, am I just dredging up a tired old argument that's been around for centuries? And second, have economists in fact done extensive work on this issue---using real data---and have they arrived at a conclusion that puts all of this to rest?

It is obviously true that technology has been advancing for centuries. The fear that machines would create unemployment has indeed come up repeatedly---going back at least as far as the Luddite revolt in 1812. And, yes, it is true: I am arguing that "this time is different."

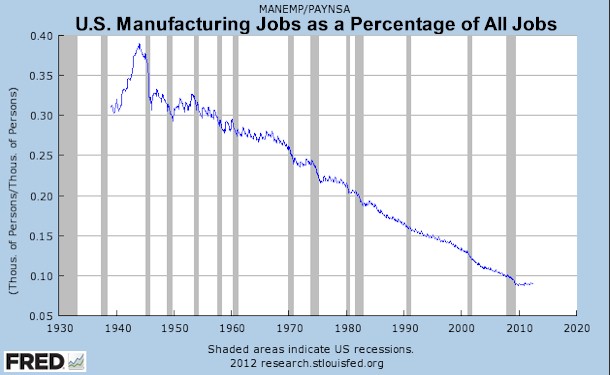

The reason I'm making that argument is that technology---or at least information technology in particular---has clearly been accelerating and will continue to do for some time to come. (* see end note)

Suppose you get in your car and drive for an hour. You start going at 5 mph and then you double your speed every ten minutes. So for the six ten-minute intervals, you would be traveling at 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and if you and your car are up to it, 160 mph.

Now, you could say "hey, I just drove for an hour and my speed has been increasing the entire time," and that would basically be correct. But that doesn't capture the fact that you've covered an extraordinary distance in those last few minutes. And, the fact that you didn't get a speeding ticket in the first 50 minutes really might not be such a good predictor of the future.

Among economists and people who work in finance it seems to be almost reflexive to dismiss anyone who says "this time is different." I think that makes sense where we're dealing with things like human behaviour or market psychology. If you're talking about asset bubbles, for example, then it's most likely true: things will NEVER be different. But I question whether you can apply that to a technological issue. With technology things are ALWAYS different. Impossible things suddenly become possible all the time; that's the way technology works. And it seems to me that the question of whether machines will someday out-compete the average worker is primarily a technological, not an economic, question.

The second question is whether economists have really studied this issue at length---and by that I mean specifically the potential impact of accelerating technical progress on the worker-machine relationship. I could not find much evidence of such work. In honesty, I did not do a comprehensive search of the literature, so it's certainly possible I missed a lot of existing research, and I invite any interested economists to point this out in the comments.

One paper I did find, and I think it is well-regarded, is the one by David H. Autor, Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane: "The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration," published in

The Quarterly Journal of Economics in November 2003. (

PDF here). This paper analyzed the impact of computer technology on jobs over the 38 years between 1960 and 1998.

The paper points out that computers (at least from 1960-1998) were primarily geared toward performing routine and repetitive tasks. It then concludes that computer technology is most likely to substitute for those workers who perform, well, routine and repetitive tasks.

In fairness, the paper does point out (in a footnote) that work on more advanced technologies, such as neural networks, is underway. There is no discussion, however, of the fact that computing power is advancing exponentially and of what this might imply for the future. (It does incorporate falling costs, but I could not find evidence that it gives much consideration to increasing capability. It should be clear to anyone that today's computers are BOTH cheaper and far more capable than those that existed years ago.).

Are there other papers that focus on how accelerating technology will likely alter the way that machines can be substituted for workers in the future? Perhaps, but I haven't found them.

A more general question is: Why is there not more discussion of this issue among economists? I see little or nothing in the blogosphere and even less in academic journals. Take a look at the contents of recent issues of

The Quarterly Journal of Economics. I can find nothing regarding this issue, but a number of subjects that might almost be considered "freakonomics."

The thing is that I think this is an important question. If, as I have suggested, some component of the employment out there is technological unemployment, and if that will in fact worsen over time, then the implications are pretty dire. Increasing structural unemployment would clearly spawn even more cyclical unemployment as spending falls---risking a deflationary spiral.

Consider the impact on entitlements. The already disturbing projections for Medicare and Social Security must surely incorporate some assumptions regarding unemployment levels and payroll tax receipts. What if those assumptions are optimistic?

Likewise, I think economists would agree that the best way for developed countries to get their debt burdens under control is to maximize economic growth. If we got into a situation where unemployment not only remained high but actually increased over time, the impact on consumer confidence would be highly negative. Then where would GDP growth come from?

It seems to me that, from the point of view of a skeptical economist, this issue should be treated almost like the possibility of something like nuclear terrorism: Hopefully, the probability of its actual occurence is very low, but the consequences of such an occurence are so dire that it has to be given some attention.

So, again, I wonder why this issue is ignored by most economists. There are a few exceptions, of course. Greg Clark at UC Davis had

his article in the Washington Post. And Robin Hason at GMU

wrote a paper on the subject of machine intelligence. I don't agree with Hanson's conclusions, but clearly he understands the implications of exponential progress.

Why not more interest in this subject? Perhaps: (A) Conclusive research has really been done, and I've missed it. or (B) Economists think this level of technology is science fiction and just dismiss it. or (C) Maybe economists just accept what they learn in grad school and genuinely don't feel there's any need to do any research into this area. Maybe something like this is so far out of the mainstream as to be a "career killer" (sort of like cold fusion research).

Another issue may be the seemingly complete dominance of econometrics within the economics profession. Anything that strays from being based on rigorous analysis of hard data is likely to be regarded as speculative fluff, and that probably makes it very difficult to do work in this area. The problem is that the available data is often years or even decades old.

If any real economists drop by, please do leave your thoughts in the comments.

___________________________

* Just a brief note on the acceleration I'm talking about (which is generally expressed as "Moore's Law"). There is some debate about how long this can continue. However, I don't think we have to worry that Moore's Law is in imminent danger of falling apart because if it were, that would be reflected in Intel's market valuation, since their whole product line would quickly get commoditized.

Here's what I wrote in

The Lights in the Tunnel (

Free PDF -- looks great on your iPhone) regarding the future of Moore's Law:

How confident can we be that Moore’s Law will continue to be sustainable in the coming years and decades? Evidence suggests that it is likely to hold true for the foreseeable future. At some point, current technologies will run into a fundamental limit as the transistors on computer chips are reduced in size until they approach the size of individual molecules or atoms. However, by that time, completely new technologies may be available. As this book was being written, Stanford University announced that scientists there had managed to encode the letters “S” and “U” within the interference patterns of quantum electron waves. In other words, they were able to encode digital information within particles smaller than atoms. Advances such as this may well form the foundation of future information technologies in the area of quantum computing; this will take computer engineering into the realm of individual atoms and even subatomic particles.

Even if such breakthroughs don’t arrive in time, and integrated circuit fabrication technology does eventually hit a physical limit, it seems very likely that the focus would simply shift from building faster individual processors to instead linking large numbers of inexpensive, commoditized processors together in parallel architectures. As we’ll see in the next section, this is already happening to a significant degree, but if Moore’s Law eventually runs out of steam, parallel processing may well become the primary focus for building more capable computers.

Even if the historical doubling pace of Moore’s Law does someday prove to be unsustainable, there is no reason to believe that progress would halt or even become linear in nature. If the pace fell off so that doubling took four years (or even longer) rather than the current two years, that would still be an exponential progression that would bring about staggering future gains in computing power.